PLASTICS

This body of work interrogates the detrimental impact of plastics on living organisms and the environment.

First as interloper, a reality that we have become disturbingly accustomed to, plastic objects and remnants exist as a predominant aspect of the landscape that is in recognizable form - boldly there.

As these interlopers degrade they become plastic as mimicker. Mysterious fragments woven in to the landscape, which require close contemplation to determine their identity, or micro fragments of less than 5 millimetres that pose as soft horrifying contributions to the earth and life; such silt, sand, or the stomach's of cetaceans.

And finally they exist as plastic as invisibles - nanoplastics that cannot be seen by the naked eye but insidiously impregnate all things living.

First as interloper, a reality that we have become disturbingly accustomed to, plastic objects and remnants exist as a predominant aspect of the landscape that is in recognizable form - boldly there.

As these interlopers degrade they become plastic as mimicker. Mysterious fragments woven in to the landscape, which require close contemplation to determine their identity, or micro fragments of less than 5 millimetres that pose as soft horrifying contributions to the earth and life; such silt, sand, or the stomach's of cetaceans.

And finally they exist as plastic as invisibles - nanoplastics that cannot be seen by the naked eye but insidiously impregnate all things living.

|

In 2018 my study of plastics emerged in a work titled Meltdown, which responds to the 2010 Olympics, held in Vancouver. While the Olympics was a celebratory, connective human experience it simultaneously contributed to issues of marginalization, consumptive excess and material waste.

Even with significant evidence of global warming and associated impact of plastics, formed acrylic was used to create a frozen world of pseudo-ice sheets and structures for various events. When the Olympics concluded manufacturers were required to manage the dismantling, recycling or disposal of materials they had created. Prior to shredding I acquired a few acrylic sheets from the manufacturer. Using these materials to create Meltdown, the single-use, acrylic ice of the Olympics operates as metaphor for the world’s disappearing ice and glaciers. |

TENDER RITUALS

I am compelled by the transformative affect of physical objects and the environment. Viewing fragments of wood, timbers, offcuts, bones, and detritus as collectables, I embrace this “collection” in my practice.

I rediscover objects like a gear from the Vancouver Sun press plant where my grandfather and cousin were pressmen, a core sample from the foundation of our home, wood and timbers from botanical gardens, my home or from loved ones, fishing buoys and bones while in Iceland.

As I remove bark, cut, sand, buff, oil or torch my treasures, a sense of time and life-experience emerges through all sorts of beautiful markings — disease, blade cuts, damage, growth rings, and disintegrated materials. My work is done by hand and I feel that my process, a form of revealing, cleansing and working is a celebration and honouring of life, perhaps reminiscent of death rituals held by many cultures.

Through this investigation I question my own experiences, sense of place and time, responsibility for the people and environments that surround me, how I function and how my actions are complicit in activities and belief systems.

I rediscover objects like a gear from the Vancouver Sun press plant where my grandfather and cousin were pressmen, a core sample from the foundation of our home, wood and timbers from botanical gardens, my home or from loved ones, fishing buoys and bones while in Iceland.

As I remove bark, cut, sand, buff, oil or torch my treasures, a sense of time and life-experience emerges through all sorts of beautiful markings — disease, blade cuts, damage, growth rings, and disintegrated materials. My work is done by hand and I feel that my process, a form of revealing, cleansing and working is a celebration and honouring of life, perhaps reminiscent of death rituals held by many cultures.

Through this investigation I question my own experiences, sense of place and time, responsibility for the people and environments that surround me, how I function and how my actions are complicit in activities and belief systems.

|

|

SALISH SEA: J35 LESS 1

This work situates us in a time where the eco-system of the Salish Sea is threatened by a variety of factors, including the highly debated Trans Mountain pipeline project. If approved, this project would create a seven-fold increase in the number of oil takers moving through these waters and would negatively impact the feeding practices of a small pod of endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales.

In this midst of the environmental, socio-political, and economic debate about the Salish Sea, female Southern Resident Orca Tahlequah (J35) gave birth to the first, albeit short-lived, surviving calf that her population has had in three years. In an act of what scientists called “a tour of grief” J35 carried her dead calf for 17 days for a distance of more than 1,600 km. Simultaneously 3 year old Orca Scarlet (J50), also a member of the same pod, was identified as being emaciated and ailing, prompting a large scale effort by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration to work with partner agencies such as the Vancouver Aquarium, to attempt medical treatment in the wild. J50 was declared dead mid-September, 2018. Through wide-spread media reporting, the plight of J35 and J50 captured the hearts of millions and highlighted the larger threat to their species and the Salish Sea as a whole.

In this midst of the environmental, socio-political, and economic debate about the Salish Sea, female Southern Resident Orca Tahlequah (J35) gave birth to the first, albeit short-lived, surviving calf that her population has had in three years. In an act of what scientists called “a tour of grief” J35 carried her dead calf for 17 days for a distance of more than 1,600 km. Simultaneously 3 year old Orca Scarlet (J50), also a member of the same pod, was identified as being emaciated and ailing, prompting a large scale effort by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration to work with partner agencies such as the Vancouver Aquarium, to attempt medical treatment in the wild. J50 was declared dead mid-September, 2018. Through wide-spread media reporting, the plight of J35 and J50 captured the hearts of millions and highlighted the larger threat to their species and the Salish Sea as a whole.

BY A THREAD

|

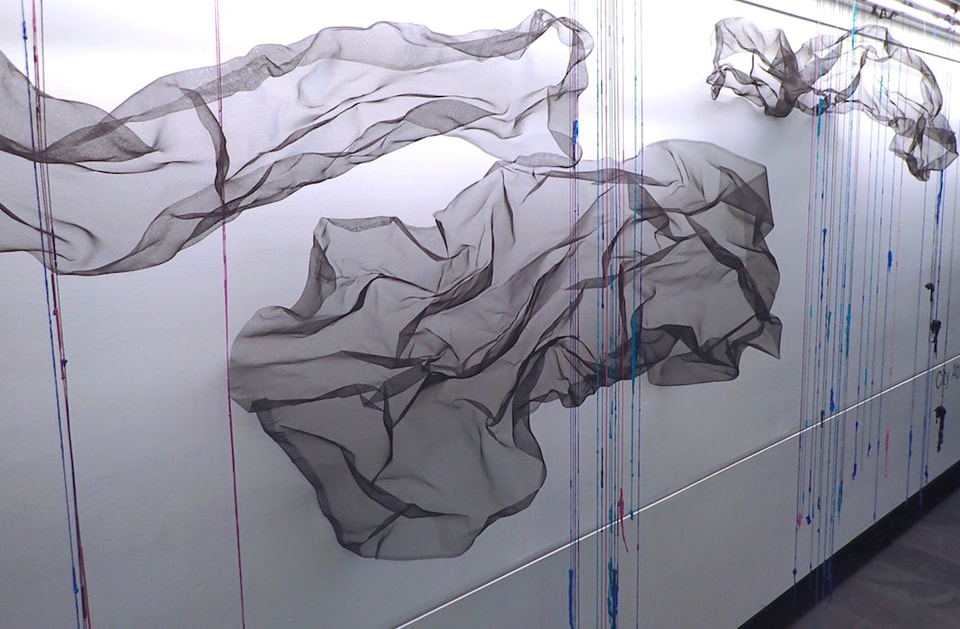

The labryinthine installation, By a Thread, explores the notion that the dominant western social condition is one of a continuous state of desire.

We take action to satisfy our yearnings, whether consumptive, intellectual, existential, or experiential, but only achieve momentary relief before desire resurfaces, forcing us to reinitiate or search, a quest that has been exacerbated by technologies such as online search mechanisms. For some this ongoing quest may be a comfortable meditative condition, but for others perhaps the opposite. Historically and within popular culture, the maze or labyrinth has operated as metaphor for questioning, searching, or confusion. In this work hundreds of strands of yarn dipped in acrylic paint hang from the ceiling to create pathways of colour, a contradictory environment where calmness, beauty or the poetic co-exist with confusion and disorientation. While moving through the work viewers' spatial norms alter as their body and line of sight shifts. Perfectly aligned rows of yarn morph from a singular line to a voluminous disorienting form. Optics and balance are challenged when equiluminant day-glo colours -- a reference to technology and the colourful strands found inside fibre-optic cable -- advance, recede and vibrate, ultimately creating an illusory sense of movement and tenuousness, while simultaneously being aesthetically engaging. This search is one without resolve as the path begins where it ends. |

MOTHER TONGUE: SURREY

This artwork is a response to news articles and research on the cultural significance of language, Canada’s linguistic diversity, and the preservation of endangered languages. It gives expression to the complex human geography of the City of Surrey by drawing on Statistics Canada census data, with the data-set Mother Tongue — standing in as metaphor for communication, an indicator of diversity and origin, and as a data-visualization tool.

To visualize the diversity of Surrey, the percentage of people reporting a specific language as their Mother Tongue is translated into a volume of paint, each with its own colour. These volumes are transformed into yarn dipped in paint, or paint poured into sheets, globs, or spots. English, at 51.72% is represented by the wall of the “white cube” itself, notionally bringing the architecture of the space into the work.

To visualize the diversity of Surrey, the percentage of people reporting a specific language as their Mother Tongue is translated into a volume of paint, each with its own colour. These volumes are transformed into yarn dipped in paint, or paint poured into sheets, globs, or spots. English, at 51.72% is represented by the wall of the “white cube” itself, notionally bringing the architecture of the space into the work.

PORTFOLIO - SELECTED COLLABORATIONS

BEARING WITNESS

|

Roxanne Charles | Debbie Westergaard Tuepah

During Surrey Art Gallery's 2018 Connecting Threads exhibition, Bearing Witness invited the public to consider Bear Creek Park, home to one of Surrey's few remaining alluvial forests. Bearing Witness was included in the body of work that resulted in Surrey Art Gallery’s Award for Outstanding Achievement in Education, specifically for its Indigenous contemporary art education and engagement, at the Canadian Museums Association (CMA) 2019 National Conference in Toronto. In the atrium of Surrey Art Gallery, a 17x10’ wall and 20’ walkway were transformed into large looms upon which approximately 400 contributors tied, knotted, braided or wove upcycled and recycled materials into fungal forms, berries, creatures, salmon roe, forest or water, with many school groups also participating in educational programs. This textile-based, alluvial forest seeks to demonstrate that through positive actions, large or small, we can collectively make a difference. From the need to improve salmon spawning in streams, to the importance of the nutrients and water provided by creeks and rivers that feed our trees, which in turn clean our air and create oxygen, this installation not only recognizes the interconnectedness of nature, honours the small amount of remaining alluvial forest within the City of Surrey, but also celebrates and bears witness to the overall power of collaboration, mindfulness, actions, beliefs, and behaviours in all facets of life. |

UNWHITEWASHED

Roxanne Charles | Debbie Westergaard Tuepah

In the midst of Canada's 150th year anniversary Unwhitewashed interrogates P'qauls, the "white rock of White Rock Beach" in the context of the lands and culture that is the White Rock of today, as contrasted to it's expansive history as home to indigenous peoples for more than 10,000 years. Embodying great historical and current significance to the Semiahmoo people, the rock has, over time, become an iconic 'whitewashed' landmark on today's White Rock beach.

Led by artist Roxanne Charles of the Semiahmoo Nation in collaboration with Debbie Westergaard Tuepah, a first generation Canadian of Danish descent, this work symbolically gives voice to oral and written histories of the Semiahmoo people.

Unwhitewashed seeks to generate dialogue and understanding relating to land rights and concepts of place, the current realities of ownership over the rock itself, and issues ranging from the Semiahmoo people's rights to drinking water through to modes of self-recognition as they relate to truth and reconciliation.

In the midst of Canada's 150th year anniversary Unwhitewashed interrogates P'qauls, the "white rock of White Rock Beach" in the context of the lands and culture that is the White Rock of today, as contrasted to it's expansive history as home to indigenous peoples for more than 10,000 years. Embodying great historical and current significance to the Semiahmoo people, the rock has, over time, become an iconic 'whitewashed' landmark on today's White Rock beach.

Led by artist Roxanne Charles of the Semiahmoo Nation in collaboration with Debbie Westergaard Tuepah, a first generation Canadian of Danish descent, this work symbolically gives voice to oral and written histories of the Semiahmoo people.

Unwhitewashed seeks to generate dialogue and understanding relating to land rights and concepts of place, the current realities of ownership over the rock itself, and issues ranging from the Semiahmoo people's rights to drinking water through to modes of self-recognition as they relate to truth and reconciliation.

THE NETWORK

Carlyn Yandle / Debbie Westergaard Tuepah

The Network, an ongoing public participation project has been included in multiple venues with hundreds of people contributing the sculpture’s growth. Created from coloured strands of synthetic waste materials like plastic and polyester, The Network is a public-engagement-driven, in-progress 3 dimensional work that operates as both an opportunity for and visual representation of actual social interaction.

Resembling something between free-form macramé sculpture and an electronic conduit system this work can be viewed as a symbol of the often fragmented, unpredictable nature of open dialogue, with ‘threads’ of conversation joining into other tangents, tangling into dead-end knots or left dangling like a sentence fragment.

The first strands of The Network came together in 2011, borne out of the general belief that there is no substitute for physical social interaction, and that when the hands are busy in rote activity, conversation flows. As with dialogue or the world wide web, this project has no logical end but contains the inherent possibility of infinite growth and complexity, as lines are woven into area and volume.

The no-barriers fabrication method — simply knotting one strand to another — allows anyone to join the conversation by simply tying one on, creating an opportunity for people of different subgroups to participate in a shared activity in the same physical space. Artists Carlyn Yandle and Debbie Tuepah perform the role of IT support: retying loose ends or securing lines of communication, all while retaining the integrity of each user’s activity.

The Network was profiled in Leanne Prain’s book, “Strange Material: Storytelling Through Textiles”.

The Network, an ongoing public participation project has been included in multiple venues with hundreds of people contributing the sculpture’s growth. Created from coloured strands of synthetic waste materials like plastic and polyester, The Network is a public-engagement-driven, in-progress 3 dimensional work that operates as both an opportunity for and visual representation of actual social interaction.

Resembling something between free-form macramé sculpture and an electronic conduit system this work can be viewed as a symbol of the often fragmented, unpredictable nature of open dialogue, with ‘threads’ of conversation joining into other tangents, tangling into dead-end knots or left dangling like a sentence fragment.

The first strands of The Network came together in 2011, borne out of the general belief that there is no substitute for physical social interaction, and that when the hands are busy in rote activity, conversation flows. As with dialogue or the world wide web, this project has no logical end but contains the inherent possibility of infinite growth and complexity, as lines are woven into area and volume.

The no-barriers fabrication method — simply knotting one strand to another — allows anyone to join the conversation by simply tying one on, creating an opportunity for people of different subgroups to participate in a shared activity in the same physical space. Artists Carlyn Yandle and Debbie Tuepah perform the role of IT support: retying loose ends or securing lines of communication, all while retaining the integrity of each user’s activity.

The Network was profiled in Leanne Prain’s book, “Strange Material: Storytelling Through Textiles”.